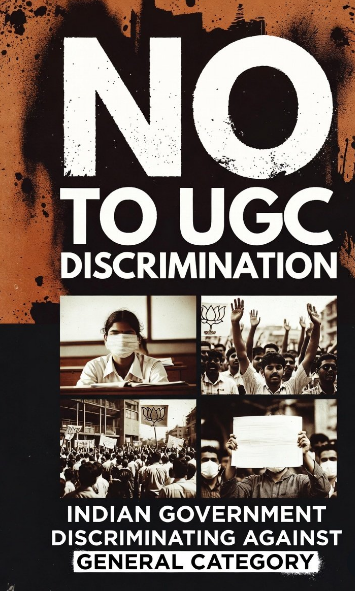

At a time when anger among general category (GC) communities is palpable, it is striking that several BJP leaders — instead of engaging with legitimate concerns — are choosing to defend the University Grants Commission’s Promotion of Equity in Higher Education Institutions Regulations, 2026 with arguments that collapse under basic constitutional scrutiny.

The most prominent of these defences, articulated by BJP MP Nishikant Dubey, relies on selective constitutional references, rhetorical shortcuts, and moral deflection rather than legal reasoning. A point-by-point examination reveals why this defence is not merely weak, but counterproductive.

Much of the justification hinges on invoking Article 15 of the Constitution, often presented as a conclusive shield against criticism. This is misleading.

Article 15 indeed prohibits discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth. At the same time, clauses 15(3) to 15(6) allow the State to make special provisions for women, socially and educationally backward classes, SCs, STs, and economically weaker sections. These clauses enable affirmative action — they do not abolish equality as a governing principle.

Crucially, Article 14 — equality before the law and equal protection of laws — continues to apply to all state action, including regulations framed under Article 15. Courts have consistently held that affirmative action must still meet tests of reasonableness, proportionality, and non-arbitrariness. Simply invoking Article 15 does not place a regulation beyond constitutional challenge.

Presenting Article 15 as an all-purpose justification — while ignoring Article 14 entirely — reflects either a serious misunderstanding of constitutional structure or a deliberate attempt to shut down debate.

Another argument advanced is that fears of misuse are exaggerated, since laws like the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act exist despite Article 15.

This comparison is flawed.

The Atrocities Act is a parliamentary statute, debated extensively, refined through amendments, and interpreted repeatedly by courts. It contains procedural architecture — including defined offences, judicial oversight, and evolving safeguards against misuse.

By contrast, the UGC equity regulations:

In fact, earlier draft language that contemplated consequences for false complaints was reportedly diluted in the final version. Comparing a mature criminal statute to a regulatory framework lacking equivalent procedural protections is not reassurance — it is evasion.

Some defenders cite a 2023 UGC letter advising institutions not to discriminate against any caste as proof of neutrality.

This argument does not withstand legal scrutiny.

A letter or advisory has no statutory force. It cannot override or neutralise binding regulations notified by the government. The 2026 UGC regulations are legally enforceable instruments; universities face penalties for non-compliance.

If the regulations themselves create asymmetries in committee composition, grievance handling, or presumptions of harm, no prior advisory can cure that defect. The correct forum for resolving such contradictions is judicial review — not rhetorical reassurance.

Perhaps the weakest argument is the moral accounting claim: “We gave EWS to general category students — so why the outrage?”

This conflates two entirely different domains.

EWS reservation addresses access to seats and opportunities based on economic criteria. The UGC equity regulations govern disciplinary processes, institutional surveillance, and grievance adjudication. One does not offset the other.

Granting a benefit does not entitle the state to design procedures that:

If benefit-granting were a licence for procedural imbalance, then the far greater scale of reservations and protections extended to reserved categories would logically justify reciprocal mechanisms against them — a proposition no serious constitutionalist would endorse.

Opposition to these regulations is not opposition to equity. It is opposition to asymmetric process.

The concern is not that discrimination should go unaddressed — it must be addressed decisively. The concern is whether:

By refusing to engage with these questions, BJP leaders risk converting a legitimate anti-discrimination effort into a legitimacy crisis.

Politically, this defensiveness is baffling.

General category communities may lack street-level mobilisation power, but they occupy crucial institutional, academic, and narrative spaces. Their resentment does not erupt — it withdraws. And when that withdrawal calcifies, governments lose not votes overnight, but legitimacy over time.

By choosing justification over correction, the BJP is not merely misreading constitutional law — it is misreading its own support base.

The Constitution allows affirmative action.

It does not allow procedural inequality.

Equity cannot be built on imbalance, nor justice on presumption. If the UGC regulations cannot withstand scrutiny under Articles 14 and 15 together, then the problem lies not with those questioning them — but with those defending them uncritically.

A government confident in its civilisational and constitutional commitments should welcome such scrutiny, not dismiss it.