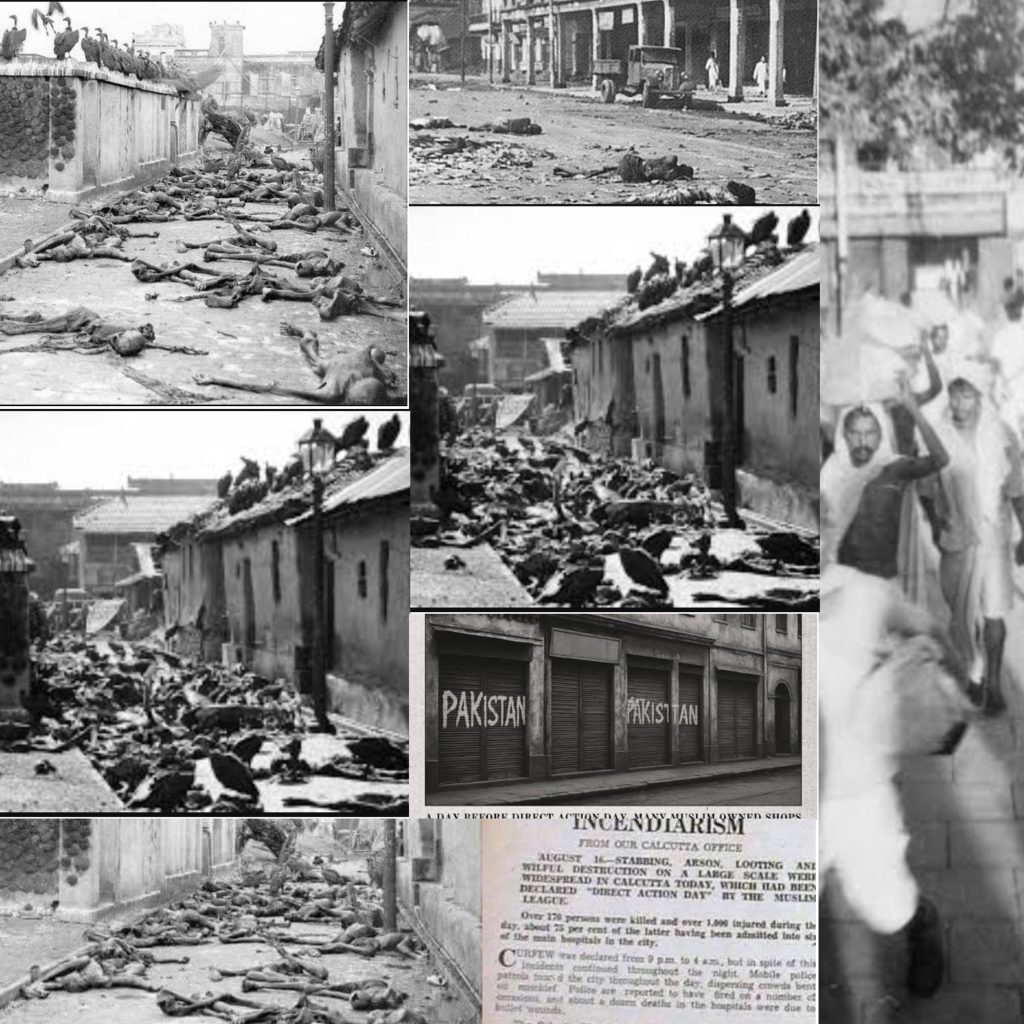

Day 1 – 16 August 1946

The whole day, the air was uneasy. Uncomfortable rumours of violence had spread faster than tramcars. Suhrawardy’s voice blared over Calcutta, and I could sense the mood turning ugly. I have long been uncomfortable with the Muslim League’s mindset—aggressive, self-righteous, looking for a chance to strike. My own Graham Road neighbourhood in Tollygunge remained quiet, but whispers came from the north—murder, loot, and worse. After sundown, veterans from Beleghata led by Toton Da (Jaideep Adhikari) came to me. Their words were clear and urgent: “It is not safe. We must assemble.” I could not sleep that night.

Day 2 – 17 August 1946

This morning I set out with Toton Da and a few of our fellow soldiers, all of whom were angry and cursing me for building my house in the middle of nowhere. We moved cautiously towards Beleghata. From there, in small numbers, we pressed on towards Ultadanga. Two skirmishes came came our way. The discipline of service never leaves you; three muslim hooligans were neutralised before they could harm more innocents. In Ultadanga I found what shook me more than combat: a great crowd of displaced Hindus, housed by Hindu Mahasabha volunteers in a makeshift relief camp. Women and children sat huddled, their eyes hollow. That night, we veterans decided to stand guard. Until a proper guard company could be formed, we would be the line. By midnight, order had begun to take shape.

Day 3 – 18 August 1946

At dawn, the Mahasabha leaders called upon us. Veterans were to guide Hindu volunteers into the worst-hit belts—Rajabazar, Moulali, Sealdah, Metiabruz, Park Circus. My charge: Rajabazar, Sealdah, Moulali. We crammed into a taxi, eight men with weapons and blades, cursing the cramped ride, the weight of arms pressing into ribs and knees. The moment we disembarked, words ended. The sights were beyond description. Hacked corpses of Hindus strewn across the roads. At Moulali crossing, a woman lay dead, her body gashed, stripped bare. No shame left, not even for the dead

We broke into small ad-hoc teams of 8–10, each led by veterans at the front. The alleys were hell. Rescue meant combat. Muslims criminals, and gangsters fought hand to hand—slashing, stabbing, hurling stones and glass. I had no chance to aim at distance. Sometimes the blade was faster.

The young people often lost their patience upon seeing Hindu women victims of sexual torture, in the narrow lanes of the broader Sealdah region, going towards Chitpur, we found a woman who was murdered and an iron rod was still sticking out from between her legs. There was no time to inspect further as Islamists charged us with bladed weapons. In another room, a seven-year-old Hindu child, chained like an animal, clothes ripped, staring blankly into nothing. We cut the chain. We brought him out. The impatient youth often became victims of well planned stabbings and attacks. A bright eyed 22 year old boy got stabbed through the gut with a spear. It look him 20 minutes to die in agony as his intestines were spilling out. I never got to ask his name. No mercy was asked and none were given. Yet we restrained the Hindu youth who wanted blind vengeance. We veterans ensured retaliation was measured—against armed men, not women or children. Still, we fought like trapped animals till well after dark. By dusk the tide had turned.

Day 4 – 19 August 1946

Sealdah sector again, but this time for rescue. No pitched combat today. Only escorting frightened families out of unsafe lanes. No action, only the heavy silence of ruins.

Day 5 – 20 August 1946

Beleghata relief operations. Carrying food, escorting survivors. No action. No fighting. But the misery was enough to break a man’s heart.

Day 6 – 21 August 1946

Entally. Narrow lanes, open drains filled with butchered parts of Hindu men, women, and children. The stench of death. The cruelty of men beyond description. This day was brutal. In one lane alone, 27 Muslims had to be shot. We spared no adult male. We could not. Not after what we saw. The youth fought like devils, but it was the veterans who steadied them, kept them from falling into madness. Operating in narrow lanes, you had to behave like a soldier if you wanted to live. It was nearly impossible to get stable footing in the slippery streets. By nightfall, Entally too was secured. Day 7 – 22 August 1946 The streets are calmer. Rescue patrols continue, but organised guards now hold their lines. The city breathes again. I close this week’s account with one thought : they thought us helpless. They slaughtered and dishonoured without shame. But when we stood together, disciplined and resolute, the tide turned. Yes, more of them died in those final days than us. But truth be told—they got far less than what they deserved.