When the Supreme Court stayed the UGC Equity Regulations, 2026, a section of the General (Unreserved) Caste community exhaled in visible relief. Social media declared victory. Protests were hailed as having “worked.” But this relief is illusory. The stay does not vindicate the General Caste. It does not correct the injustice embedded in the regulations. And it certainly does not address the deeper constitutional wound the guidelines have opened.

If anything, the stay exposes how General Caste Indians exist in a constitutional blind spot, present everywhere in obligations, absent in protections.

Let us be clear.

The Supreme Court did not stay the UGC Equity Guidelines because they were unfair to the General Caste.

It did not stay them because protests erupted.

And it did not stay them because the Court suddenly discovered “reverse discrimination.”

The stay was granted on technical and constitutional grounds:

In short, the Court paused the regulations because they were dangerously drafted, not because they were morally questioned.

This distinction matters. Because a badly drafted law can be fixed.

A fundamentally exclusionary philosophy often is not.

The most revealing moment came from the bench’s oral observation, widely paraphrased as above.

This sentence should disturb every General Caste citizen not because it is legally improper, but because it is politically and socially revealing.

The Court was saying:

Public anger is irrelevant to constitutional scrutiny.

That is correct in law.

But here is the uncomfortable subtext:

When reserved-category movements protest, they are often framed as struggles for dignity.

When the General Caste protests, they are framed as noise — something the Court explicitly distances itself from.

This is not judicial bias. It is social reality leaking into institutional language.

The General Caste is not viewed as a vulnerable group capable of being wronged structurally only as a demographic that must adjust.

For the first time, a central regulation in higher education:

This was not affirmative action.

This was asymmetric justice.

Affirmative action is about compensatory inclusion.

The UGC Equity framework went further — it redefined equity as caste-exclusive protection.

Under the guidelines:

That is not social justice.

That is institutionalised inequality under the banner of equity.

The stay does not strike down the philosophy behind the regulations.

It merely postpones its implementation.

So what exactly has been won?

Nothing durable. Nothing principled. Nothing protective.

This moment feels familiar because it is.

General Caste students poured onto the streets.

Some burned themselves alive.

The State listened — but did not stop.

The courts ultimately upheld OBC reservations after 2 years.

Lesson: Protest does not equal protection.

Again, General Caste students protested in unprecedented numbers.

Again, the courts allowed the policy to proceed after an initial stay order.

Lesson: Merit arguments do not override social policy.

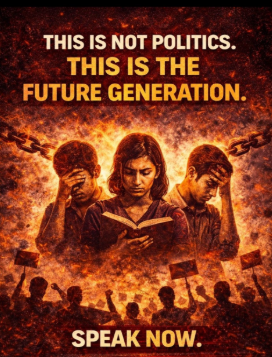

Now the General Caste protests against exclusion from protection itself.

And once again:

History suggests one thing clearly:

The system rarely rolls back policies once they are ideologically anchored.

The real problem is not this regulation.

The real problem is that the General Caste has been written out of the moral vocabulary of justice.

There is no accepted framework to even articulate General Caste vulnerability without moral suspicion.

And that is why this stay feels hollow.

The Supreme Court’s stay is a procedural brake, not a moral course correction.

Until Indian policy acknowledges that:

The General Caste will continue to exist as a constitutional obligation holder, not a constitutional rights bearer.

This is not a demand for privilege.

It is a demand for equal protection under law — nothing more, nothing less.

And a stay, however dramatic, does not deliver that.